Ceci n'est pas un Proust

Or, Notes on Reading in Time

“But did he ever murder anyone, Dostoievsky? The novels of his that I know might all be called The Story of a Crime. It’s an obsession with him, it isn’t natural that he should always be talking about it.”

“I don’t think so, dear Albertine. I know little about his life. It’s certain that, like everyone else, he was acquainted with sin, in one form or another, and probably in a form which the laws condemn…. All that sort of thing seems to me as remote from myself as possible, unless there are parts of myself of which I know nothing, for we realize our own nature only in the course of time.”

-Marcel Proust, The Captive

I wanted to be closer to reality, by which I meant physical, concrete reality and for me the visual always came first, also when I was writing and reading, it was what was behind letters that interested me. When I was outdoors, walking, like now, what I saw gave me nothing. Snow was snow, trees were trees. It was only when I saw a picture of snow or of trees that they were endowed with meaning…. This was the problem with all representation, of course, for no eye is uncontaminated, no gaze is blank, nothing is seen the way it is. And in this encounter the question of art’s meaning as a whole was forced to the surface…. But all the meaning I extracted from it came from me, I charged it with something of mine.

-Karl Ove Knausgaard, My Struggle: Book Two

The key, then, is indebtedness. The key is connectedness.

-Cynthia Ozick, “The Boys in the Alley, the Disappearing Readers, and the Novel’s Ghostly Twin”

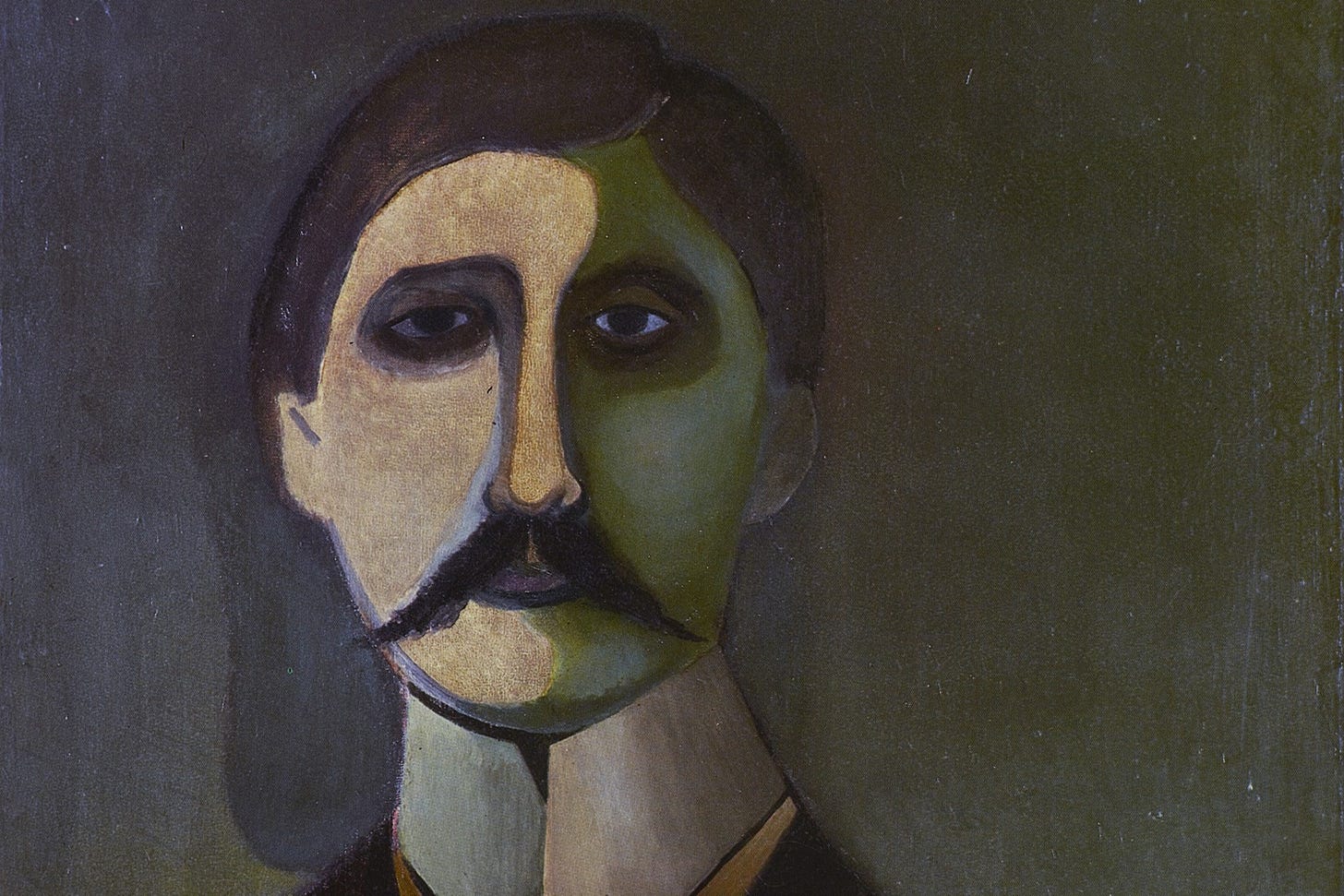

It took me six years to read In Search of Lost Time. This was by choice. I’m an unusually ambitious reader, but the prospect of tackling Marcel Proust’s seven-volume, 1.26 million-word magnum opus all in one go seemed a bit much even for me. Surely, I thought, it would be better to space the volumes out, to give Proust – and myself – a little room to breathe.

So, from 2013-2018, I read one volume a year.1 I was reading Proust as I neared the bittersweet end of my undergraduate degree at the University of Alabama (Swann’s Way), reading him throughout an aimless – and at the time seemingly endless – Ben Braddock period that followed upon my return to Texas (Within a Budding Grove, The Guermantes Way), reading him when, with some help from my future wife, I started to figure out my shit (Sodom and Gomorrah), reading him breathlessly as I returned to school to start my Master’s in English lit (The Captive, The Fugitive), reading him as I eagerly worked toward a budding academic career that died before it could bloom (Time Regained). A critical stretch of my life has been forever marked by my progression through In Search of Lost Time.

This staggered approach to Proust could, I suppose, be seen as an admission of defeat, were it not possible to justify it on thematic grounds. True, forgotten details of plot and character plagued me from volume to volume, making it all the more easy for me to end up entangled in Proust’s famously sprawling sentences. But I gained something from the experience, too – the novel’s thematic concerns, its meditations on time and on memory, filtered in more organically than they otherwise would have. In this sense, I didn’t just read Proust – I lived him.

My point is simple, even obvious: time is different when reading. Or, as Philip Roth more succinctly put it, “Life is long and art is shorter.” Proust’s maximalist style (shared by progeny like Karl Ove Knausgaard in his “anti-Proust” epic, My Struggle) draws attention to a quality fundamental to all narrative art: that, in the moment of reading, watching, or listening, “real” time, lived-in time, is stopped, displaced in favor of a manufactured timeline. Life-time is hollowed out and replaced by fiction-time, which operates according to its own rules, which is to say the dictates of the work. What Proust makes particularly salient – and this revelation continually returns to haunt me, over a decade after the experiment first began – is that fiction is a parlor trick that transforms time, or at least bends it to its will. And there’s something else, too, something that I’ve only recently come to truly understand: that reading, just as it transforms fiction-time, transforms life-time too.

Great art is a landscape, a planet, a cosmos: it makes and unmakes realities. It allows us to really see ourselves through the time and space it affords us to consider others: carefully, thoughtfully, and at great length. But who are the others that we come to know? And who are the selves we come to see?

Reading is by nature a solitary activity. Despite the mediators who might weigh in on a book before, during, and after the fact – teachers and peers, reviewers and critics, book clubs and Bookstagrams and BookToks – the ultimate encounter is always between the individual reader and the text at hand. Mediators are essential, but, in the moment of the act of reading, there can be nothing between the reader and the text.

In 2007, Cynthia Ozick argued that the decline of literary criticism – that is, of the literary critic as a distinct figure in the public consciousness – had had a deleterious effect on the health of American literary culture, and on the American novel in particular. Without knowledgeable, trusted critical voices, she argued, readers would lack the context necessary to fully appreciate not only the literary novel as a form, but why it mattered:

Novels, however they may manifest themselves, will never be lacking. What is missing is a powerfully persuasive, and pervasive, intuition for how they are connected, what they portend in the aggregate, how they comprise and color an era. A novel, it goes without saying, is an idiosyncrasy: it stands alone, it intends originality – and if it is commandeered by genius, it will shout originality. Yet the novels that crop up in any given period are like the individual nerves that make up a distinct but variegated sensation, or act in chorus to catch a face or a tone. What is missing is an undercurrent, or call it, rather (because so much rests on it), an infrastructure, of serious criticism.

What is essential is a critical mass of critics pursuing the kind of criticism that can define, or prompt, or inspire, or at least intuit, what is happening in a culture in a given time frame.

But for unfulfilled readers and writers who fret over the neglect of the literary novel, something instinctually different might begin to hover: a hint of innate kinship, a backdrop, the white noise of the era that claims us all. In times that are made conscious of the air they breathe – a consciousness that only a critical infrastructure can supply – the varieties of literary experience become less antagonistic than inquisitively receptive.

The better question is not who will read, or how they will read, but why.

For a particular type of reader, the absence of critical infrastructure Ozick identified seventeen years ago has become a howling void. What a “critical mass of critics” might once have offered us – a picture of the consciousness of the age, rendered in fiction – has all but vanished not just in practice, but also in theory. Stitching things together, putting them in order, has come to be seen as an impossible fantasy. We all seem resigned to our fate. All any individual reader can do is grab whatever little scrap of wreckage is at hand and hold on.

To this end, mainstream reading culture has collapsed in on itself, generally in the least interesting possible way. The real substance of literature prized by critics like Cynthia Ozick and, say, Susan Sontag – the constituent parts of particularity and idiosyncrasy that, in sum, form a view of a coherent, dynamic whole – has been eroded in favor of buzzwords and checklists and arbitrary tests, any of which can, at a moment’s notice, toss out entire works, authors, or schools of writing based on real or imagined infractions, regardless of any other qualities they might possess. The vision of growing, shifting, living canon that Ozick and Sontag once advocated has been shaved down into a series of predictable one-note lists, a culture of small-minded, hyper-individualistic approaches to reading. The qualities most prized in the novel now are typically not literary at all, but the qualities of fast fashion and self-help.

I am on record defending the role of the critic and attacking the half-visible coalition of institutional forces degrading how art is produced, consumed, and understood. The priorities of many readers – on “relatability,” on “likeability,” on the degree to which a given work is “written for” them – often seem to me to be hopelessly displaced, breeding a species of small-minded narcissism that limits the horizons and constrains the imagination. Such readers are not really readers at all, but consumers, and the function of a consumer is to be party to a transaction. They can only exchange, only buy and sell.

The widespread disinterest in critical consciousness, cast off in favor of the immediate surface-level question whether the reader is being adequately served by their reading, damns us all to an understanding of literature so shallow and so limited that it can’t help but seem pointless. Anyone can make a purchase; anyone can consume and fill out a survey on their level of satisfaction on a scale of 1-10. But I also believe that anyone can think more broadly and deeply about that hopelessly old-fashioned thing that used to be called “the human condition” through the prism of literary art, and find a sense of meaning and purpose in doing so. The fashionable question – “who is art for?” – is infinitely less interesting than that older, more universal question: “What is art for?”

But then, those questions are not so easily separated, for questions of what and who are always inextricably intertwined. One can develop a sense of “literature” outside of the reader’s experience, outside of the self, but the immediate experience of the self and the infinite sweep of the not-self are not, of course, wholly separate, and never have been. Marcel Proust understood this; so did James Joyce, in Ulysses – “Think you’re escaping and run into yourself. Longest way round is shortest way home” – and in his use of Dublin as a locale for all of his magnificently intricate fictions:

For myself, I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal.

In Joyce, William Faulkner found the model for his Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, drawn from his own “little postage stamp of native soil” in Oxford and its environs, as well as his torrents of stream-of-consciousness prose; Toni Morrison drew on both of these writers to recover, reconstruct, and reimagine Black American histories that for centuries had been stolen, distorted, and violently suppressed, and in doing so helping to create space for the continual expansion of the literary canon to perspectives once excised from the official representations of the tenor of the age. The point of recognizing this influence is not to downplay Morrison’s achievement, any more than highlighting Joyce’s use of Henrik Ibsen would devalue the magnificent dramatic sweep of the “Circe” episode of Ulysses. The point is to note that the particular and the universal are never so wholly separate as either the individualists or identitarians would have you believe. The full range of human experience is both infinite and radically constrained.

The universal and particular, the individual and community, and the artist and audience must continually enrich each other to be healthy, and to have their full effect. Joyce, Faulkner, and Morrison – and all truly great writers – infuse what’s hyper-particular in their experience with a vast universality, and it’s this that gives them their significance. The critic, by uncovering and documenting the genealogies of this experience, demonstrates this (or should demonstrate it) to the common reader, providing the knowledge essential to developing readers who are more than consumers – and more than themselves. Such is the task of the critic.

Even under ideal conditions, however, there are some limits to her reach. For one, there is the division between, as highlighted by Ozick, between the critic and her audience: essential knowledge can only be instilled in an audience if it can be reached. The teacher is critical, but without a student there can be no teacher. And, again, there is that persistent problem of mediators. In the moment of reading, there is only the self and the text. So, if it’s true that the most valuable literary interventions are those that arrive from outside the self, ready and waiting to infuse and expand it, one must ask: what if the doors into the self are all shut? What happens to the world outside the self, when it arrives to find a self closed off from the world?

I’m repeating my Proust strategy with Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle. This year I’ll read Book Five, which means I’ll finish with Book Six in 2025. Like Proust, Knausgaard practices a kind of radical subjectivity, but his digressions are more granular, more quotidian, and less discriminate in their accumulation of seemingly meaningless detail. He walks the streets and wonders if the pram he’s pushing makes him appear as emasculated as he feels; he drifts disinterestedly from room to room at a child’s birthday party; he eats, drinks, shits, writes, teaches, tries and tries and tries and fails to get laid. The material of My Struggle is infused with meaning only through accumulation; in this, fiction-time mimics life-time with staggering, thrilling precision.

For me, part of fiction’s appeal is in how it helps the mind resist absorption into the everyday. Boring in Knausgaard isn’t boring at all; Knausgaard boring is richer than real boring, than boring boring, and thus whenever possible I try to supplant the latter with the former. This being the case, a preoccupation with reading fiction might be seen as a desire to arrest the slow march of time, or to stop it completely, before (presumably) regaining it for the purpose of critically examining the present. To really get to the bottom of things.

Prose doesn’t change. Reading is an exercise in returning, again and again, to the same well. It’s akin to sculpting, slowly chipping away at a block of text to reveal the forms hidden within. But this is all an illusion, an exercise with value but lacking in the ability to achieve its ultimate goal – to understand the world, and to know yourself.

You know the rhythms of literature. The thrill of their challenges, the familiarity of their comforts. But the rhythms of literature are not the rhythms of life; there is a correlation but not an exact correspondence, and over time you can come to mistake one for the other. You spend six years reading Proust and you are married. You spend six years reading Knausgaard and you are divorced. This is life-time: you’ve changed, and the world has changed. But the text which constructs your fiction-time remains exactly the same.

The American Modern Library edition of In Search of Lost Time combines the fifth and sixth volumes of the French edition into one, hence the volume/year disparity.