Picasso / Warhol: Whose Era?

Or, Genius and the Individual Brand

This New York Review of Books article on Picasso’s legacy, by art critic Jed Perl, is worth your time. The occasion is the current spate of exhibitions and retrospectives commemorating the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death, but the purpose is to reexamine, through Picasso, how recent cultural shifts have altered the public perception of the figure of the artist. I found it very compelling.

To Perl, much of the current public conversation surrounding Picasso is partly a referendum on a particular view of artistic creation. The artist in the Picasso mode, he argues, is both public and intensely private, deeply knowledgeable of art history and highly conscious of their place within it, proficient in a wide variety of media and styles, and motivated by a deeply personal vision. Their overwhelming concern is for the work of art not merely as entertainment, polemic, or furnishment, but as a work of art – that is, as the thing itself. This view could be called “traditional,” but its most essential characteristic may be that it leaves room for the idea of genius.

Artists or art granted the “genius” label are afforded certain privileges. They can make demands of their audience. Rather than cater to existing tastes, they force a different perception by way of challenge and provocation. Deeper engagement with work of genius is rewarded by the clarity and intensity of their vision, a way of seeing that, once learned, provides an authentically new vision of the world for the viewer, reader, or listener. At its most potent, work of genius is inexhaustible, continually offering up new shades of color and meaning.

Perl believes – correctly, I think – that this understanding of art, if not the idea of genius, is in danger of being displaced. At minimum, it is being challenged, with a constellation of cultural, political, and economic forces aligning in opposition to it – forces of which Andy Warhol is emblematic.

Warhol, unlike Picasso, is primarily interested in novelty – or, to put it more charitably, in the pleasure of immediate recognition. His Campbell’s soup cans and portraits are fundamentally exercises in style, visually distinctive but shallow. To illustrate this, Perl cites Warhol’s roster of apparently unrelated portrait subjects. The only qualities uniting Marilyn Monroe, Prince, and Mao Zedong are that the audience already knows their faces – and that those faces are now presented with indifference. The result of this approach is a shift in focus away from the artist and their work to the audience and its reception; art becomes a primarily public, social experience, with a value derived almost exclusively from the ambient judgments of the crowd. Like an advertisement, all of the value of a given work of art is tied up in the attention it attracts. Warhol’s conception of the artist is not as a visionary, but as a brand.

The embrace of the Warhol philosophy – let’s call it “Warholism” – has become incredibly widespread. It can be found everywhere, from a recent dissent by Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan to a Hannah Gadsby-curated Picasso exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, nauseatingly titled It’s Pablo-matic (Barf!). There is immense cultural, economic, and – increasingly – ideological pressure to treat art as a commodity, a mere reflection of the viewer’s self, with no greater purpose or higher meaning, unless the words “purpose” or “meaning” can be incorporated into a particular branded experience.

Individuals, in Warhol’s world, can be one of two things: part of the crowd, or “famous for fifteen minutes” – that is, the temporary object of passive, ironic (dis)interest. This limits the possibilities of what can be represented to what gets immediate attention, true. But, more importantly, they narrow the scope of how subjects can be represented, thereby reducing art’s ability to speak meaningfully to the varied shades of human experience.

An artist touched by genius – an artist like Picasso – cultivates intimacy with their audience on an individual-by-individual basis, using private space as a tool of connection. The modern iteration of Warholism gives the illusion of intimacy, promising to facilitate connection, along with meaningful democratic choice. But the fruits of this are only made available to those willing to shave off pieces of themselves and put them on display, with the ultimate effect of eradicating the distinctions between the public and private sphere. The former becomes subordinate to a warped version of the latter, with the full range of aesthetic judgment, historical context, and artistic struggle all collapsed into mere personal taste – a personal taste that is always being broadcasted.

If anything, Perl understates the degree to which Warholism has infiltrated American culture. It extends well beyond the museums, beyond Kagan, Gadsby, and the stupid, tedious hordes of “anti-woke” culture war drones who only exist to mirror them, deep into the popular image of the self. For the individual, reducing art to its Warholist elements reduces it to a means of expressing one’s own personal style, to “pieces of flair,” as opposed to a distinct, independent sphere of perception. It’s a Van Gogh travel mug, a Shakespeare t-shirt, a Clarice Lispector tote bag. Warhol’s world is a world in which the potential for a sustained and intimate connection with art becomes impossible, overwhelmed by a flurry of private trivialities. His audience is the crowd, and a crowd cannot connect. The most it can do is recognize.

Not that Warhol, personal expression, or even commodification are necessarily bad things in themselves. People are drawn to them for a reason: namely, they’re fun. I’d be a hypocrite if I said otherwise – I have a William Faulkner poster in my office and a James Joyce necktie in my closet. But the distinction between art and reproduction, between Picasso and Warhol, must still be drawn. The relationship I have with my James Joyce tie is very different from my relationships with Dubliners or Ulysses. Those relationships are much more involved, more difficult, and more complex; in some ways, they more closely resemble relationships with people than with fiction. They change and evolve, continuously challenging and enlightening and renewing themselves, and it’s this aspect of the relationship that makes it truly valuable. Recognition can bring simple pleasure, but it’s no substitute for exquisite complexity.

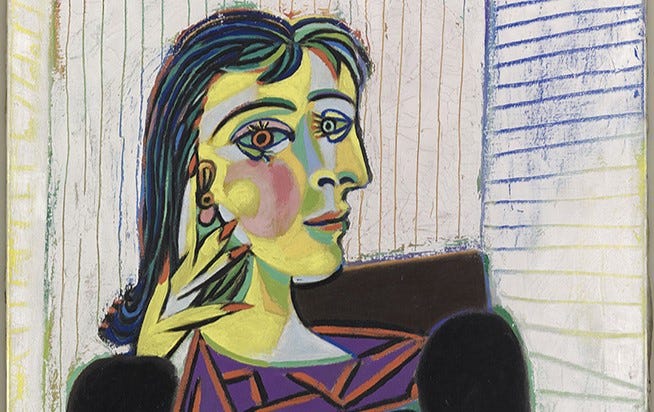

I’ll end with a bit more hypocrisy – specifically, with a personal anecdote. On our honeymoon in Paris, my wife and I visited several art museums (as one does). We saw what must have been hundreds of great works, and plenty of well-known masterpieces. But the most powerful artistic encounter I had – one of the most powerful artistic experiences I’ve ever had, anywhere – was with the Portrait of Dora Maar (1937) at the Musée Picasso.

Even in a space full of Picasso’s work, the Portrait made an immediate, distinct impression. I’m not sure I can even convey that feeling – suffice to say that something about the painting connected viscerally with me. There was a draw to it, an enigma I could sense within that I was eager to unlock. And the experience was all mine. I’m not sure it could have been shared, or that I even tried to share it. (Though maybe I should have.)

The power of that initial impression never went away. In fact, it deepened with time. Who was this person? Who was Dora Maar, really? I turned the questions over in my mind, consciously and unconsciously. Basic biographical information helped. She was one of Picasso’s mistresses. She was an artist in her own right. She chafed at how he portrayed her. Knowing all this helped, but it didn’t really get at the heart of the thing. Dora Maar was a troubled, difficult, and fascinating person, who had a troubled, difficult, and fascinating relationship with another troubled, difficult, and fascinating person. And all of that seemed to be ambiently contained here, in this single painted image.

What drew me to the Portrait, I think, was that it conveyed something about the essential character of Picasso’s relationship with Dora Maar. There’s something of both of them in it, a tiny piece of their highly specific shared history. The Portrait commemorates a kind of a conspiracy between artist and subject – a conspiracy into which I was invited. Somehow, I understood this immediately and instinctively, and it permanently altered things in some indefinable way. There’s the world before the Portrait, and the world after. The two are not the same.

Part of me is still there at the Musée Picasso, standing before the Portrait of Dora Maar. Studying it. Drinking her in, drinking the two of them in.

The clarity of his vision still anchors me there.