Dylan Planet

A tribute to Bob Dylan, a visit to the Bob Dylan Center.

With Dylan, so much has been said about him, it's difficult to say anything about him that hasn't already been said, and say it better. Suffice it to say Dylan is a planet to be explored. For a songwriter, Dylan is as essential as a hammer and nails and a saw are to a carpenter…. His journey as a songwriter is the stuff of myth, because he lives within the ether of the songs.

Not everyone gets Bobby, but those who do get him deep.

-Joan Baez

You have to learn to be a cartographer. With an artist like Bob Dylan, the terrain is too vast, the topography too varied, to navigate without a map.

For over 60 years now, songs, performances, and recordings have been accumulating like layers of sediment. Dylan recognizes the distinctions between them – how songs change as they move through time, carrying the past with them even as they fashion it anew – but has little respect for the idea that music should be a monument to some particular idea or expression or moment. His work is a living thing. It’s always changing, and the landscape’s composition is a matter of perspective. Every grain of sand is a mountain; every mountain just a grain of sand.

Dylan is a giant, of course. Not just as a lyricist, not just as a songwriter, but as an elemental creative force. He’s raw and ragged and can never be grasped in full. When writing about him, it’s tempting to lapse into reverence and easy to drift into abstraction. But the impulse to draw on image, symbol, and signifier must be harnessed, not embraced; controlled, not succumbed to. You don’t become a sailor by diving into the sea.

If what I’m saying is evocative but doesn’t quite make literal sense, that’s good. That’s Dylan. The elusiveness has always been part of the package, and besides, there are plenty of others who’ve said it before, said it better. I’m no historian and barely a critic; all I can offer are fleeting impressions, glimpses of my map of Planet Dylan.

We all have our own Bob Dylan. Mine reveals himself in a verse of his 2009 song “I Feel a Change Coming On”:

I’m listening to Billy Joe Shaver,

And I’m reading James Joyce.

Some people they tell me

I’ve got the blood of the land in my voice.

He’s all there, in those four lines: the journeyman songwriter, the visionary poet, the voice that thrums at the frequency of history, the utter subjectivity of it all. Dylan’s body of work swirls around this hard core like an aural kaleidoscope, reflecting and refracting itself to reveal plump gold nuggets you swore weren’t there before. But they are there, right in your face, glittering with something plain, ancient, and undeniable. There’s always some new truth swimming up from the depths, insisting on being heard.

I first heard Bob Dylan – really heard him – in “Ballad of a Thin Man”. There was rage, righteous rage, but with Dylan it wasn’t the raw, inchoate anger of a punk. It was literate, coherently expressed, and dripping with the contempt of a young man determined to overthrow, reshape, and remold the established order. It was also exactly what I needed at 17. Dylan spoke to my intelligence, my anger, my arrogance, and my sense that the world was bigger, weirder, and more full of possibility than I’d realized. Something is happening and you don’t know what it is.

That was the draw at first. I had a lot of feelings I had to channel somewhere, so I channeled them into Dylan. The pounding piano riff of “Thin Man” thundered deep in my head and chest; when I wanted to bite back at my would-be masters, I let “Maggie’s Farm” do the biting; when I felt trapped in the special hell that is adolescence, “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” was the road across a new and better landscape. I raged along to “Like A Rolling Stone,” belting the refrain from the windows of my truck as I drove through the North Texas suburbs, and felt free. I picked up a guitar and learned to play it, inhabiting those songs as much as I could, infusing myself into them and them into myself.

I kept listening as I finished high school and left for college. Playing Dylan songs became a way of connecting with people, one that continued well after graduation. Dylan was always there, a trusted confidante, informing, challenging, questioning, searching. When I needed it, Planet Dylan was ready for me to beam down.

Youth, by nature, burns out quickly. Dylan’s youthful rage endures, but his real staying power is in how he speaks to maturity. Though his songs routinely venture into the past, they aren’t about nostalgia. They encompass not just those elusive moments of freedom but ghosts that remain once they’ve passed. The songs illuminate lives lived in secret, realities that never were and could never be, the old age already latent in youth, and the youthful fires that keep burning in the caverns of old age. If it’s eternal and eternally changing, you can find it in Dylan.

Another way of saying it: wherever I go, Dylan is already there.

Colossal Dylan likenesses flank the Bob Dylan Center: imprinted on the brick exterior, towering over either side of the entrance enclave, looming seriously at various accent points in the lobby and gift shop. Something is happening here, these sentries seem to say, but you don’t know what it is. But where “Ballad of a Thin Man” taunts, the Bob Dylan Center invites. Come on in and step right up.

Once Center staff have scanned your tickets and given you a headset, they shuffle you into a panoramic theater showing an introductory film. The theater is connected to another room, a better room. The walls of this room carry you chronologically through Dylan’s life and art, offering a potent mixture of familiar and new images, videos, recordings, and paraphernalia – hand- and typewritten lyrics sheets, articles of clothing, rare and obscure promotional material – while, in the center of the space, six pillars dive deep into the writing, recording, performance, and reception of six individual songs. There’s a lot of treasure there – the magic words are “previously unknown” – and more on the second floor, including selections from the Bob Dylan Archive, another theater, this one showcasing video of rare performances, and an exhibition gallery. In my three and a half hours there, I soaked up as much as I could.

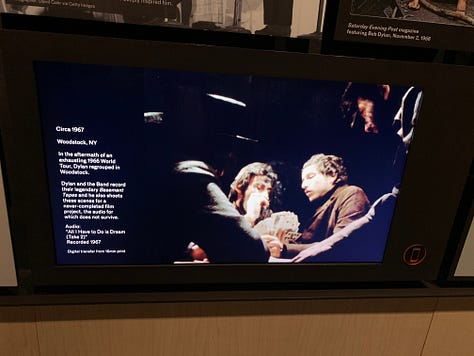

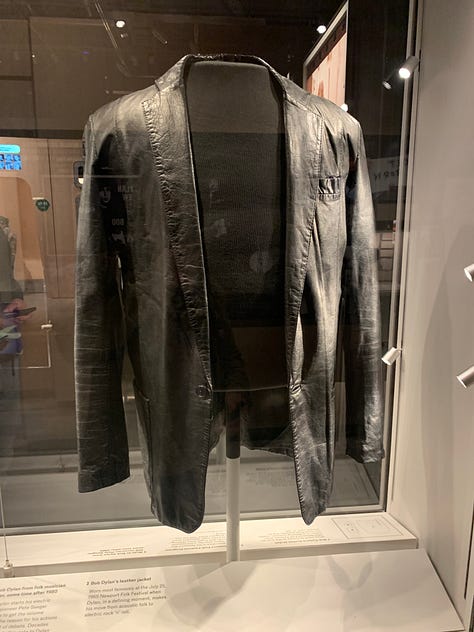

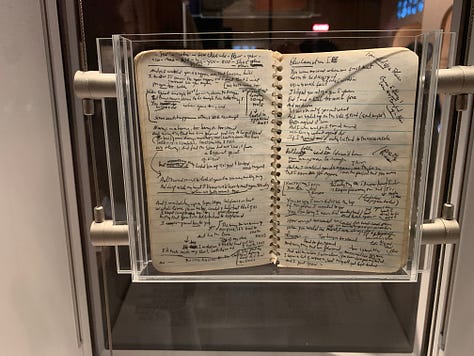

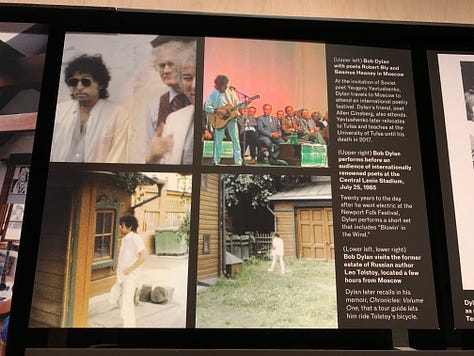

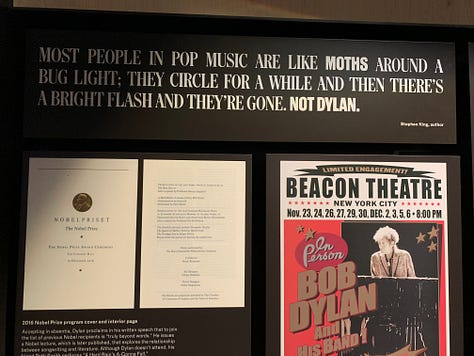

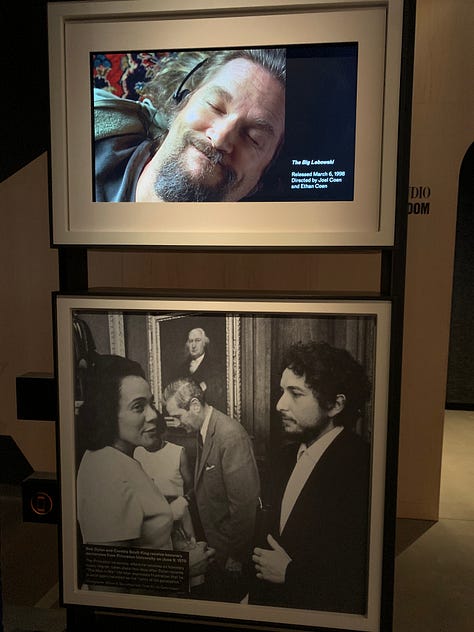

I can only recount highlights, impressions, discoveries. The surviving footage from a lost Basement Tapes-era film project; a rare live performance of “Not Dark Yet”; stunning outtakes from Shot of Love and World Gone Wrong. The leather jacket Dylan wore when he went electric at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival; the notebooks in which he drafted Blood on the Tracks. The Elvis Costello-curated jukebox experience of Dylaniana; surprise appearances by Seamus Heaney and Stephen King. The delightfully weird non sequiturs and flashes of humor, most memorably the union, forged by “The Man in Me,” of Coretta Scott King and The Big Lebowski. In this context, even the familiar studio versions of Dylan standards like “Tangled Up in Blue” and “Like a Rolling Stone” hit different. Re-infused with so much history, they paradoxically feel fresh and new again.

The Bob Dylan Center – and its massive Archive, only 2% of which has been cataloged – is a satellite outpost, beaming in signals from the creative mass that is Dylan Planet. It’s history, art, creativity as carnival. It captures what makes Dylan compelling without sacrificing his significant mystique.

The song displays are centerpieces – literally – and, I think, they capture the general dynamic quite well. Museum representatives have said this installation will evolve; during my visit, the inaugural set was still in place: “Chimes of Freedom,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Not Dark Yet,” “The Man in Me,” “Tangled Up in Blue,” and “Jokerman.” A mix of well-known and slightly deeper cuts, these songs are presented as lyric sheets, studio and live performances, moments of history, and moments in time, giving the impression of comprehensiveness. Everything’s laid out right there in front of you, up to and including the end product – just scan with your little modified iPod and let it flow into your headset. But, once you listen, you realize that the bits of historical ephemera are red herrings, and that the songs can never really be resolved or explained, any more than you could resolve or explain Everest or the Amazon or the Cliffs of Moher. Any attempt can only be an approximation, a partial stand-in for the thing itself.

Oddly enough, the six songs are presented non-chronologically. The songs are displayed in the order I listed them, meaning the natural progression from 1965’s “Like a Rolling Stone” to 1970’s “The Man in Me” is interrupted by “Not Dark Yet,” released in 1997. It’s a minor thing, but there’s something maddening about it. The songs are almost presented in order of release, but not quite. Where is the logic in this? Why the approximation, when exactitude would have come just as easily?

Maybe it’s nothing; maybe there is no real reason. It seems to me that the irreverence of this move – the lack of respect for chronology, the refusal to come to a close and fully resolve – communicates something essential about Bob Dylan, though I can’t quite say what. His refusal to settle into history, maybe; the refusal, like that other Dylan, to go gently into the good night. Loose threads, loose ends, inconsistencies, and deliberate anachronisms are how these songs have remained so alive for so long. The last verse of “Spirit On the Water” comes to mind: You think I’m over the hill? You think I’m past my prime? Let’s see what you got. We can have a whoppin’ good time.

I keep coming back to the end of my time on the first floor of the Dylan Center. If you follow the wall to its end, you’ll reach the final scan: an audio recording of Dylan reading the conclusion of his Nobel lecture:

So what does it all mean? Myself and a lot of other songwriters have been influenced by these very same themes. And they can mean a lot of different things. If a song moves you, that’s all that’s important. I don’t have to know what a song means. I’ve written all kinds of things into my songs. And I’m not going to worry about it – what it all means. When Melville put all his Old Testament, biblical references, scientific theories, Protestant doctrines, and all that knowledge of the sea and sailing ships and whales into one story, I don’t think he would have worried about it either – what it all means.

John Donne as well, the poet-priest who lived in the time of Shakespeare, wrote these words: “The Sestos and Abydos of her breasts. Not of two lovers, but two loves, the nests.” I don’t know what it means, either. But it sounds good. And you want your songs to sound good.

When Odysseus in The Odyssey visits the famed warrior Achilles in the underworld, Achilles – who traded a long life full of peace and contentment for a short one full of honor and glory – tells Odysseus it was all a mistake. “I just died, that’s all.” There was no honor. No immortality. And that if he could, he would choose to go back and be a lowly slave to a tenant farmer on earth rather than be what he is, a king in the land of the dead. That whatever his struggles of life were, they were preferable to being here in this dead place.

And that’s what songs are, too. Our songs are alive in the land of the living. But songs are unlike literature. They’re meant to be sung, not read. The words in Shakespeare’s plays were meant to be acted on the stage. Just as lyrics in songs are meant to be sung, not read on a page. And I hope some of you get the chance to listen to these lyrics the way they were intended to be heard: in concert or on record or however people are listening to songs these days. I return once again to Homer, who says, “Sing in me, O Muse, and through me tell the story.”

It was elating, listening to Bob Dylan narrate the sum of his own achievement. As I moved across the room, I collapsed back into the version of myself that first encountered “Ballad of a Thin Man” at 17, passing along the way through every other self that had since taken bread and meat from Dylan’s table. That was the apex of the visit for me. For a moment, I knew who and what I was: a land surveyor, a cartographer, still mapping the expanse of Planet Dylan.

“I’ve got the blood of the land in my voice.” Oh my god.

This is a great read. Thank you. I had no idea the Center even existed, but mostly it is always a joy to find someone who both “gets Bobby” and can express it well.