ChatWSB

Reading William S. Burroughs in the Age of A.I.

I think that words are an around-the-world, oxcart way of doing things, awkward instruments, and they will be laid aside eventually, probably sooner than we think. This is something that will happen in the space age. Most serious writers refuse to make themselves available to the things that technology is doing. I’ve never been able to understand this sort of fear. -William S. Burroughs, 1965

The thinking machine runs out of thought, and sucks the brains out of everybody with stainless steel needles glittering in pinball pinks and gas flares and sky rockets. -Word

There was a period last summer when I could read only Naked Lunch. Its myriad excesses were surprisingly comfortable; the maelstrom of fear and paranoia, ecstasy and withdrawal, psychosexual acrobatics, secret agents, insect and alien life forms, extreme violence, heightened absurdity, and elaborate conspiracy, all rendered in a torrent of clinical, hardboiled prose, seemed to be an appropriate psychic landscape for a difficult season. Better yet, there was no troublesome narrative or meddling underlying order a la Joyce or Pynchon – just pure, sweet chaos for me to inhabit. At times Naked Lunch bordered on a religion, or at least a path to self-actualization. The Complete All American Deanxietized Man, c’est moi.

Now, thankfully, I’m no longer in a state of such distress, but my interest in William S. Burroughs persists. The terrain of Naked Lunch and other Burroughs fictions feels familiar in the sociopolitical environment of 2025. In fact, the more Burroughs I read, the more his interest in the relationship between human beings and technology – particularly mass communications technology – feels like an important overlooked addition to the current ongoing discourse about recent advances in so-called Artificial Intelligence.

We are well into the computer age, to the point where terms like “computer age” now seem archaic, but new technologies continue to emerge with the potential to radically change human perception. Generative A.I. is, of course, the most prominent of these. Already, the story goes, it has spurred major disruption in several industries; already its existence has significantly contributed to our ongoing information crisis, challenging an already embattled linguistic, political, economic, and social order. The ease with which anyone can now spontaneously generate large bodies of text, images and songs in almost any imaginable style, or video avatars and voice narration even of well-known public figures, coupled with the air of authority with which many seem to grant the information they receive, has contributed to a powerful sense, actively encouraged by Silicon Valley stakeholders, that A.I. is in some sense the future. It is, we are told, revolutionary.

Perhaps there’s some truth to this; very likely there are also ample reasons for skepticism. In either case, the technology and the debates surrounding it have progressed with such incredible speed that it can be difficult to even begin processing the changes that A.I. has actually brought about, much less their broader implications for society, art, and politics.

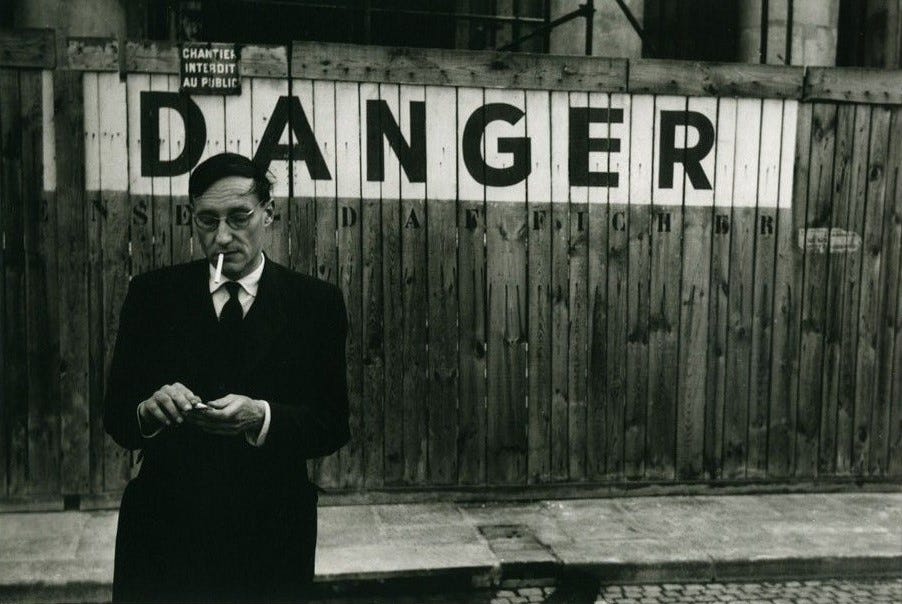

In the time I’ve spent reading William S. Burroughs over the last year, I’ve found that his fiction and thought are useful tools for giving the A.I. debate a degree of shape and definition. His work speaks to the moment, both because it anticipates the rise of the informational chaos brought about by the internet generally and generative A.I. specifically and because its attempts to reckon with that chaos challenge arguments now being put forth by A.I. boosters and A.I. skeptics alike. If you’re looking to grind an axe, as I was and am, he will readily hand you one. Nearly thirty years after his death, William S. Burroughs remains the ultimate chaos agent.

“What we call history is the history of the word. In the beginning of that history was the word.” -The Ticket That Exploded

One of Burroughs’ key preoccupations as a writer is the idea of the word. This is fitting for a writer, but Burroughs’ suspicion of the word as a basic unit of communication is perhaps unique among writers of his generation. Unlike, say, Samuel Beckett, whose meditations on the failure of language are unfailingly intricate and elegant, the embrace of cacophony and ugliness from Naked Lunch on betrays Burroughs’ deeply-held suspicion not only of conventional forms of writing, but of language itself.1

In one of his most famous formulations – “Language is a virus from outer space” – Burroughs captured a fundamental separation that exists between words and objective reality. Language, commonly assumed to operate in service of humankind, is actually an autonomous agent, parasitically attaching itself to the reality it purports to describe. In doing so, the word shapes, steers, and utterly transforms that reality, solidifying a specific, limited perception as “truth”. It adapts itself to its context, and, in doing so, is prone to corruption.

If language can determine how individuals perceive reality, then the harnessing of language by a centralized authority can, for all intents and purposes, decide the common reality in which we all live. In short, language in the wrong hands can function as a tool of authoritarian social control, and technology, particularly mass communications technology, serves as a means to this end, exacerbating humankind’s alienation from its own linguistic tools. Language is detached from objective, observable reality, existing primarily to serve entrenched interests. But, unlike in Orwell’s 1984, in which the government deliberately restricts both the nature of messages permissible in media and the expressive possibilities of language itself, authoritarians in Burroughs seek to overwhelm the populace by overwhelming them with language. Language isn’t reduced to the bare essentials a la newspeak, but overinflated and overindulged to the point of meaningless. This idea forms the basis of one of Burroughs’ core observations about postwar industrial society: that the information it produces is an effective mechanism of control by virtue of its sheer volume.

Navigating such an environment requires eradicating a certain degree of interiority and, by extension, individuality, radically reshaping the entire social order. Or, as Dr. Benway puts it in Naked Lunch: “The study of thinking machines teaches us more about the brain than we can learn by introspective methods. Western man is externalizing himself in the form of gadgets.” In his reading of Burroughs, media theorist Marshall McLuhan elaborates on this point:

The central theme of Naked Lunch is the strategy of bypassing the new electric environment by becoming an environment oneself [through hard drugs, illicit sex, and transgressive art]. The moment one achieves this environmental state all things and people are submitted to you to be processed. Whether a man takes the road of junk or the road of art, the entire world must submit to his processing. The world becomes his “content.” He programs the sensory order.

New technologies, McLuhan continues, facilitate an act of “collective cannibalism,” during which the existing social order attempts to accommodate new technological developments into itself. The process of externalization is a manifestation of our “natural bias” towards acceptance, beginning with the individual but eventually permeating society as a whole. Notably, Burroughs objected to McLuhan’s characterization of his work in a 1965 interview with The Paris Review, insisting that he instead was “aimed… outward” and seeking “as far as possible a complete awareness of surroundings.” In other words, he entirely rejected the idea of an individual component to his writing, arguing instead that it was focused the effects of the control apparatus on the entire society. But, in either case, it follows that any attempt at wresting control from such a social order must redirect this flow of information.

The capture, distortion, and redirection of the linguistic signals used in service of social control was a major part of Burroughs’ artistic project. Techniques like the “cut-up” and “fold-in” methods, by which he composed Naked Lunch and its follow-up, the Nova Trilogy (The Soft Machine, Nova Express, and The Ticket That Exploded), sought to break through this ambient cultural noise: first by intercepting it, then by overwhelming and redirecting its energies. In these books, the precise arrangement of words on the page is not determined solely by rational choice, as in conventional methods of writing, but relies to a significant extent on chance. Words, phrases, and passages are instead drawn from a large collection of typescripts (the “Word Hoard”) and reassembled, with the “final” text composed using the unexpected associations that result. As a result, the texts themselves are never quite complete and always in flux. Later techniques, such as “playback,” carried this idea even further, but the intent remains the same: to disrupt expected patterns of language and thought extensively enough to clear the way for something new.2 Burroughs’ maximalism is his attempt to both absorb the overwhelming amount of information produced by postwar society and channel it into a tool for resistance – and, in a sense, democratization.

But, again, the “Word Hoard” fictions are not systematic about the cycles of disorder they attempt to map. Too chaotic to identify or taxonomize the human condition of their age with any kind of precision, these works instead bear its imprint in their forms. In other words, the linguistic disorder of Naked Lunch, The Soft Machine, Nova Express, and The Ticket That Exploded reflects a broader technological disorder, and it’s in their sustained assault on the lack of sense and meaning produced by that very disorder that these works anticipate the widespread disruptive power of internet technologies, up to and including A.I.

Now here is a calculating machine—Of course it can process qualitative data—Color for example—I feed into the machine a blue photo passes to the Blue Section and a hundred or thousand blue photos rustle out while the machine plays blues in a blue smell of ozone blue words of all the poets flow out on ticker tape—Or feed in a thousand novels and scan out the last pages—That is quality is it not? Endingness? -Nova Express

Disruption has long been a central operating principle of Silicon Valley; the selling point of generative A.I. is in its apparent power to “disrupt” the disruption. Having cannibalized several decades’ worth of online activity, along with an indeterminate amount of additional written, visual, and aural media from before the internet era, these technologies are, much like Burroughs’ calculating machine, able to produce new material in response to written prompts. If you ask OpenAI’s ChatGPT, for example, to produce a haiku, it can do so quickly and competently:

The Large Language Models, or LLMs, on which tools like ChatGPT rely do well with simple, rigid rules – hence ChatGPT’s ability to produce a passable haiku. It even appears to be making a series of artistic choices. I only asked for a haiku; ChatGPT “decided” on the topic.3 From there, we can conclude that generative A.I. tools, when properly prompted, are capable not only of producing media that adheres to a given set of criteria, but of reasonably extrapolating to fill in the gaps.

Naturally, this capability has sparked significant debate on A.I.’s implications for the creative arts. On the one hand, A.I. boosters make grandiose predictions about using A.I. tools to produce feature films, albums, novels, and video games. Meanwhile, many artists and writers have been raising concerns about generative A.I. The exact nature of A.I.’s long-term disruptive powers notwithstanding, its implications for intellectual property, artistic integrity, and the ability of those in the creative industries to make a living now seem clear enough. And if we narrow our field of vision and ask whether this technology is capable of creating good art – of creating good writing or music or film, our mechanisms for exploring the full range of human experience both potential and actual – the answer, at this point, still seems overwhelmingly to be no.

Many of the existing critiques of A.I. as a tool of artistic creation, such as this widely-read Ted Chiang article in the New Yorker, have argued that this technology simply isn’t capable of creation in any meaningful sense. Art, according to Chiang, is the product of a series of choices, and because A.I. does not choose in the same manner that humans do, it is inherently incapable of making art. In fact, these tools work against intentionality – they are designed not to create, but to generate.

William Burroughs, to some degree, complicates this discourse. The externalizing impulse inherent in his work is antithetical to the conception of art as a mode of “expression,” in the sense that it de-emphasizes the importance of the individual artist (and reader) in the process of production and consumption. The mechanical quality of Burroughs’ cut-up method might even appear to validate the idea that new technologies can be used to create – or even generate – meaningful art. His writing, emerging as it does masses of unrelated text metabolized for the purpose of creating new text, bears some superficial resemblance to A.I.-generated prose. In this narrow sense, the difference between Naked Lunch and ChatGPT might be said to be one of scale.

Indeed, many of Burroughs’ descriptions of his own radical writing techniques suggest that he might have seen revolutionary potential in generative A.I. technology, including in all three novels of the Nova Trilogy. In The Soft Machine, Burroughs’ fold-in method is presented as a means for resisting an authoritarian force known as the Trak Agency. Trak, which also appears in Naked Lunch, is a vast operation with Reservations, a Police Force, and a large, unaccountable bureaucracy – as well as a News Agency, with which it maintains control over the broader information ecosystem. When it attempts to recruit William Lee (Burroughs’ literary alter ego) as an executive, he and his ally the Subliminal Kid mount a resistance using a version of the fold-in method:

We fold writers of all time in together and record radio programs, movie and sound tracks, TV and juke box songs all the words of the world stirring around in a cement mixer and pour in the resistance message “Calling partisans of all nation—Cut word lines—Shift linguals—Free doorways—Vibrate ‘tourists’—Word falling—Photo falling—Break through in Grey Room.” (emphasis mine)

Lee and the Subliminal Kid assimilate written, audio, and visual media, then use it to produce new material to resist a message being transmitted by Trak. This “folding in” bears a superficial resemblance to generative A.I.’s probability-based approach to text generation. However, unlike with ChatGPT or a similar tool, the method used in this passage is steered entirely by Lee and the Kid. In this case, at least, the act of creation requires a degree of intentionality, placing Burroughs much closer to Ted Chiang than he might at first appear.

The concept evolves elsewhere in the Nova Trilogy. In The Ticket That Exploded, an automated “writing machine” appears after the collapse of a societal order destroyed by a sustained informational onslaught. Presented as part of an exhibition meant to guide the public in fashioning a new symbolic language for the new world, this machine, like Lee and the Subliminal Kid’s use of an A.I.-like version of the fold-in method, is an instrument of resistance:

A writing machine that shifts one half one text and half the other through a page frame on conveyor belts. . . Shakespeare, Rimbaud, etc. permutating through page frames in constantly changing juxtaposition the machine spits out books and plays and poems — The spectators are invited to feed into the machine any pages of their own text in fifty-fifty juxtaposition with any author of their choice any pages of their choice and provided with the result in a few minutes. (emphasis mine)

Since it is only one part of a larger exhibition, the Writing Machine is able to specialize; this in turn gives the reader a chance to form a somewhat more detailed picture of how it actually operates. Most critical, however, is who is making use of the writing machine. In contrast to the Soft Machine fold-in technique, the writing machine is universally accessible, its usage not only democratized but encouraged. Users who prompt it receive their result nearly as quickly as a user of ChatGPT.

So The Soft Machine and Nova Express appear to foreshadow a technology very much like generative A.I., which is portrayed in a generally sympathetic light. But Burroughs’ interest is not only in the mechanics of the technology itself, but in how such tools might be deployed. So, while both The Soft Machine and The Ticket That Exploded suggest, pace Ted Chiang, that the techniques of A.I. do possess the ability to generate artistic artifacts of real value, they also strongly suggest that it greatly depends on what specifically is being done with those techniques – and by whom it is being done, and to what end. This is where the seeming harmony between Burroughs’ vision and our actually-existing ChatGPT future begins to erode.

Shut the whole thing right off—Silence—When you answer the machine you provide it with more recordings to be played back to your ‘enemies’ keep the whole nova machine running—The Chinese character for ‘enemy’ means to be similar to or to answer—Don’t answer the machine—Shut it off— -Nova Express

In his interview with The Paris Review, Burroughs repeatedly pushed back against common critiques of the cut-up method. Cut-up was not, as critics claimed, a novelty, but a valid means of composition that should be judged first and foremost by its outputs:

INTERVIEWER

Therefore, you’re not upset by the fact that a chimpanzee can do an abstract painting?

BURROUGHS

If he does a good one, no. People say to me, “Oh, this is all very good, but you got it by cutting up.” I say that has nothing to do with it, how I got it. What is any writing but a cut-up? Somebody has to program the machine; somebody has to do the cutting up. Remember that I first made selections. Out of hundreds of possible sentences that I might have used, I chose one.

Somebody has to program the machine; somebody has to do the cutting up. Whatever his differences with Ted Chiang and other contemporary critics of A.I., Burroughs here appears to share their belief in the pivotal role of authorial intent. This position is arguably taken out of self-interest – especially since he seems to challenge the concept even as he validates it – but, if we take him at his word, it begins to indicate the specific nature of his divergence from the position taken by contemporary A.I. boosters and other techno-optimists.

The purpose of the cut-up method was not to produce words for their own sake. In contrast with generative A.I., which aims to produce as much text as possible as frictionlessly as possible, it was extremely labor intensive, with Burroughs often cutting up and rewriting the same text multiple times. He believed cut-up was a means of penetrating through the manufactured realities constructed via the onslaught of information imposed by powerful societal actors through to the hidden reality of the world. Scrambling false “reality” would create opportunities for both writer and reader to see true Reality.

So, in this sense, the important thing about cut-up was not the text it produced, but the process itself. Engaging with the technique facilitated a new relationship to language and, in time, the emergence of a new form of consciousness. One can presume that words produced using fully automated means – through ChatGPT, say – cannot function in the same way. If anything, writing produced fully by machines might prove more suspect than writing that simply presents a false picture of reality, because machine writing is self-sustaining and self-replicating – that is, more purely like a virus – in a way that more traditional forms of text production are not. Given this, it stands to reason that purely machine-generated text compounds existing issues with the language virus. And, of course, there’s the matter of who programs the machine.

In The Ticket That Exploded and especially Nova Express, Burroughs dramatizes the struggle for narrative control between machine writing and cut-up writing – between “reality” and Reality – by imagining it as a war of attrition. The “Nova Wars” that feature prominently in both books are effectively a state of pervasive conflict between the Nova Mob, who seek to destroy planets by fostering “as many insoluble conflicts as possible” through various messaging-control mechanisms, and the Nova Police, who counteract the Mob with messages of their own. The full scale of the conflict is too vast to be summarized here, involving rival gangs, invading alien forces, disease and pestilence, roving squadrons of junky ventriloquist dummies called “Death Dwarves”, and court systems designed to regulate biological processes, but throughout both books, media, broadly defined, is an important focal point. Whoever controls the media apparatus and its many offshoots gains a significant advantage over the opposing forces. That is, large-scale mechanized message production is a core theatre in the Nova Wars.

Both the Nova Mob and Nova Police attempt to seize control of meaning-making machines. At one point in Nova Express, Biologic Agent K9, a member of the Nova Police, outlines the strategic imperatives of this struggle:

The error in enemy strategy is now obvious—It is machine strategy and the machine can be redirected. . . the machine can only repeat your instructions since it can not create anything—The operation is very technical. . .

Agent K9 goes on to describe the strategy in some detail. Throughout, he repeatedly stresses the same point that Burroughs makes above: someone has to program the machine. The machine can only repeat your instructions since it can not create anything. In other words, the machine cannot be trusted to produce meaning on its own. Only deliberate human intervention – by trained specialists, no less – can make the machine work in the interest of actual human beings. Power and control are determined not through language, but through specific uses of language.

This intervention requires the cultivation of a new consciousness. To this end, Nova Technicians are employed to manage and direct the machines, with K9 describing their responsibilities in the same terms that Burroughs often used to describe the cut-up method. Technicians think in “association blocks instead of words,” which are then expressed in the “Juxtaposition Formulae” that function as weapons in the Nova War. Basically, this is the strategy previously employed by Lee and the Subliminal Kid in The Soft Machine and by the writing machine in The Ticket That Exploded, now operating on a planetary scale. Taking over the machines allows Technicians to monitor and control the messages being dispersed by enemy forces.

But, despite their role in smashing the mind-control machine, the Nova Police are not liberators. They do not necessarily facilitate individual freedom any more than does the Nova Mob. As K9 acknowledges, “The Formulae of course control populations of the world.” This statement glides by quickly, so it’s easy to miss, but the implication is clear: the end of a controlling regime is not necessarily the end of all controlling regimes. In Burroughs, the mere existence of any mass communications apparatus is a form of coercion. These technologies, like all technologies, inevitably distort human perception, shaping the individual to their own ends – and the ends of those in control, especially if they go unchallenged.

This, I think, is a key point that needs to be made in the ongoing debates over A.I.: that, regardless of this technology’s present uses or ultimate capabilities, granting it legitimacy inevitably cedes control to its owners. There is always a cost to using ChatGPT. Viewing generative A.I. technologies as Burroughsian thought control machines may actually over-estimate their capabilities, as there are already signs that progress is slowing, from the technology’s own inherent limitations to foreign competition. But even if generative A.I. is truly inevitable, as our Silicon Valley overlords insist that it is, there is still value in challenging it, because there is inherent value in resisting any apparatus that seeks to program us into complacency. Even if we are destined to fail, it is necessary that we attempt to reprogram the machines.

You will readily understand why people will go to any lengths . . . . to avoid the hopeless dead-end horror of being just who and where you all are: dying animals on a doomed planet. -The Ticket that Exploded

I make no claims to speak from a state of enlightenment, but merely to have attempted the journey, as always with inadequate equipment and knowledge. . . falling into every possible accident and error, losing my gear and my way . . . -Burroughs to Jack Kerouac

William S. Burroughs understood that human beings are not as purely rational as we like to imagine. As such, he is useful for cultivating a true countercultural sensibility. He always operates at the frequency of the outsider. The Burroughs of the 1950s and ‘60s was operating, not always willingly, at the vanguard of some of the most significant social transformations in history; now, the world has changed, but many of the same problems he grappled with in his writing have not only persisted, but festered and metastasized. He has retained his ability to speak to the moment, because far too little has fundamentally changed.

One of the aims of all of Burroughs’ “Word Hoard” fictions is to show how technological developments place humankind at a remove from unmediated modes of experience; their method is a mechanism meant to demonstrate the means by which it occurs. By overwhelming the reader with a relentless stream of vivid, shocking, explicit, and disjointed details, Burroughs forces them to become hyper-aware of the breakdown of what Marshall McLuhan called the “sensory order,” and the degree to which it has been dulled and corrupted by technological interference. Each of his phrases is a barb that tears at complacency to get at the raw stuff underneath. Take, for instance, the beginning of the “Hassan’s Rumpus Room” chapter of Naked Lunch:

Gilt and red plush. Rococo bar backed by pink shell. The air is cloyed with a sweet evil substance like decayed honey. Men and women in evening dress sip pousse-cafés through alabaster tubes. A Near East Mugwump sits naked on a bar stool covered in pink silk. He licks warm honey from a crystal goblet with a long black tongue. His genitals are perfectly formed – circumcised cock, black shiny pubic hairs. His lips are thin and purple-blue like the lips of a penis, his eyes blank with insect calm. The Mugwump pushes a slender blond youth to a couch and strips him expertly.

“Stand up and turn around,” he orders in telegraphic pictographs. He ties the boy’s hands behind him with a red silk cord. “Tonight we make it all the way.”

“No, no!” screams the boy.

“Yes. Yes.”

There is no such thing as a “representative” Burroughs passage, but this selection – and the even more extreme pages that follow it – helps highlight a key characteristic of much of his writing. Much like other forms of avant garde prose, fragmentation, nonlinearity, stream-of-consciousness technique, and other, similar devices all work to make the reader fully conscious of the act of reading; in Burroughs, this is compounded by strange, viscerally repellent imagery and assaults on bourgeois morality and good taste. The overall effect is to work against the “natural bias” towards acceptance inculcated by technologies meant to make life frictionless.

Machine writing – writing by ChatGPT, by generative A.I. – definitionally cannot do this. LLMs have no intentions beyond fulfilling prompts as quickly and efficiently as possible; the type of disruptive writing Burroughs produced demands sustained attention, focus, imagination, and the capacity to weather intense shock, from writer and reader alike.

This is writing engineered to short-circuit acceptance and destroy complacency. The writing of William S. Burroughs cannot be assimilated.

In interviews, Burroughs frequently expressed a desire to move beyond language and communicate in “association blocks,” which he believed to be a more genuine method of communication than language.

Burroughs outlined a version of this technique in both Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded, as well as his essay “Playback from Eden to Watergate” (1973). Playback operates in three stages. First, make a recording of the target – a politician, for example, or a business of some influence – using “tape recorder one”. Then, using “tape recorder two” and “tape recorder three,” make additional recordings. Following that, splice the recordings together. Finally, play the recordings back at the target. This process, over time, would eradicate privacy and shame, shatter social inhibitions, and disrupt the social order, to the end of destroying the broadly shared vision of reality used to create social control, which, “[l]ike all control systems… depends on maintaining a monopoly position.” If the nature of reality can be asserted by anyone, then no one can control it, granting all individuals a kind of freedom – though not without adverse effects.

Of course, ChatGPT only “chose” the topic because landscapes and seasons are common in traditional haiku, much as sonnets are traditionally about love.