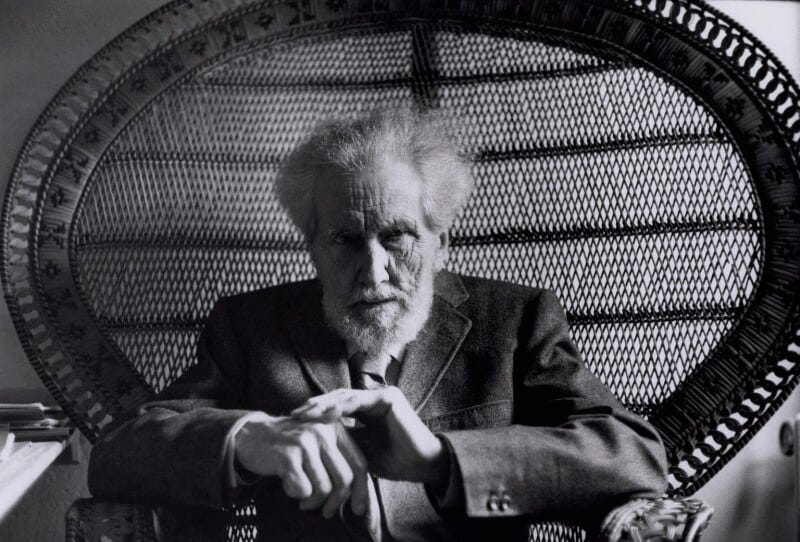

A Draft for Uncle Ez

On reading & writing Ezra Pound

Ezra Pound’s notoriety is well-earned. The longer one looks, the more one finds the charges levied against him – of treason, of anti-semitism, of ideological alignment with a wide variety of political monsters and freaks, from fascists to segregationists – to be justified, often emphatically so. As such, he is not always good company.

Charles Olson came to understand this firsthand. Among the first of Pound’s visitors at St. Elizabeths Hospital, where he was interned for twelve years following World War II, Olson wrestled with the contradiction at the heart of the older poet’s work: how he could be both “as brilliant a maker of language as we have had in our time” and “the worst kind” of fascist, the “intellectual fascist” and “filthy apologist and mouther of slogans which serve men of power.”1 Olson spent as much time with Pound as he could stand, which wasn’t much. He first visited St. Elizabeths in January 1946; by 1948, he was done, sick of Pound’s nastiness. Olson would go on to have a successful writing career; Pound spent another ten years in the asylum before his release.

I have been working and wrestling with Ezra Pound since 2017. For much of that time, I, like Olson, have found him to be unpleasant company – especially since my recent research has focused on Pound’s political activity in the 1950s. At times, it has felt like reading the Facebook feed of my worst relative, rant after rant from Crazy Uncle Ez. For better and worse, I now see echoes of him everywhere, in the chaos of our politics and the degraded state of our culture. Pound, Olson wrote, was “an exterior man. His work, too. And all his culture was so much stuff in a hole to keep the wind away.” This is perceptive, and certainly not intended as a compliment. But in the age of Trump 2.0 and the ongoing onslaught of AI, when the howling constantly threatens to drown everything else out, it can be beneficial to have some stuff in the hole.

There is something essentially American about Ezra Pound. He gets to the heart of the American character in a way few have, and perhaps ever will, embodying us at both our very best and absolute worst. The more time I spend with it, the more convinced I am that The Cantos is the great American epic poem, in the same way that the Aeneid is the great Roman epic, or the Commedia the great Italian epic. There is something in the way this poem engages with the sweep of history – not only American history, but world history, and American history as a component of world history – that places Pound and The Cantos in truly esteemed company. Even his manifest failures shimmer with the light of this achievement. Even the splintered remains of the final, unfinished fragments.

I expect I will have more to say about Pound and The Cantos very soon. Probably much more. First, though, I’ll be establishing myself as a player in the global Poundian underground. On 9 July, I will be presenting a paper at the 31st Ezra Pound International Conference at Schloss Brunnenburg, a castle owned by Pound’s descendants, in Tirolo, Italy. I will be among many formidable names in Pound Studies; I will be surrounded by arcana, by history. Notably, my presentation will take place on the 100th birthday of Pound’s daughter, the poet and scholar Mary de Rachewiltz, who will be in attendance.

I have worked very hard to get to this place, to make this happen. I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity. And I strongly feel that this is only the beginning for me – there is much more work still to be done.

新日日新

All Olson quotes are from the indispensable Charles Olson & Ezra Pound: An Encounter at St. Elizabeths, ed. Catherine Seelye. Grossman Publishers, 1975.